Fundamental theorem of algebra

In mathematics, the fundamental theorem of algebra states that every non-constant single-variable polynomial with complex coefficients has at least one complex root. Equivalently, the field of complex numbers is algebraically closed.

Sometimes, this theorem is stated as: every non-zero single-variable polynomial with complex coefficients has exactly as many complex roots as its degree, if each root is counted up to its multiplicity. Although this at first appears to be a stronger statement, it is a direct consequence of the other form of the theorem, through the use of successive polynomial division by linear factors.

In spite of its name, there is no purely algebraic proof of the theorem, since any proof must use the completeness of the reals (or some other equivalent formulation of completeness), which is not an algebraic concept. Additionally, it is not fundamental for modern algebra; its name was given at a time in which algebra was mainly about solving polynomial equations with real or complex coefficients.

Contents |

History

Peter Rothe (Petrus Roth), in his book Arithmetica Philosophica (published in 1608), wrote that a polynomial equation of degree n (with real coefficients) may have n solutions. Albert Girard, in his book L'invention nouvelle en l'Algèbre (published in 1629), asserted that a polynomial equation of degree n has n solutions, but he did not state that they had to be real numbers. Furthermore, he added that his assertion holds “unless the equation is incomplete”, by which he meant that no coefficient is equal to 0. However, when he explains in detail what he means, it is clear that he actually believes that his assertion is always true; for instance, he shows that the equation x4 = 4x − 3, although incomplete, has four solutions (counting multiplicities): 1 (twice), −1 + i√2, and −1 − i√2.

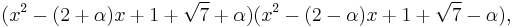

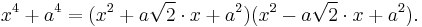

As will be mentioned again below, it follows from the fundamental theorem of algebra that every non-constant polynomial with real coefficients can be written as a product of polynomials with real coefficients whose degree is either 1 or 2. However, in 1702 Leibniz said that no polynomial of the type x4 + a4 (with a real and distinct from 0) can be written in such a way. Later, Nikolaus Bernoulli made the same assertion concerning the polynomial x4 − 4x3 + 2x2 + 4x + 4, but he got a letter from Euler in 1742[1] in which he was told that his polynomial happened to be equal to

where α is the square root of 4 + 2√7. Also, Euler mentioned that

A first attempt at proving the theorem was made by d'Alembert in 1746, but his proof was incomplete. Among other problems, it assumed implicitly a theorem (now known as Puiseux's theorem) which would not be proved until more than a century later, and furthermore the proof assumed the fundamental theorem of algebra. Other attempts were made by Euler (1749), de Foncenex (1759), Lagrange (1772), and Laplace (1795). These last four attempts assumed implicitly Girard's assertion; to be more precise, the existence of solutions was assumed and all that remained to be proved was that their form was a + bi for some real numbers a and b. In modern terms, Euler, de Foncenex, Lagrange, and Laplace were assuming the existence of a splitting field of the polynomial p(z).

At the end of the 18th century, two new proofs were published which did not assume the existence of roots. One of them, due to James Wood and mainly algebraic, was published in 1798 and it was totally ignored. Wood's proof had an algebraic gap.[2] The other one was published by Gauss in 1799 and it was mainly geometric, but it had a topological gap, filled by Alexander Ostrowski in 1920, as discussed in Smale 1981. A rigorous proof was published by Argand in 1806; it was here that, for the first time, the fundamental theorem of algebra was stated for polynomials with complex coefficients, rather than just real coefficients. Gauss produced two other proofs in 1816 and another version of his original proof in 1849.

The first textbook containing a proof of the theorem was Cauchy's Cours d'analyse de l'École Royale Polytechnique (1821). It contained Argand's proof, although Argand is not credited for it.

None of the proofs mentioned so far is constructive. It was Weierstrass who raised for the first time, in the middle of the 19th century, the problem of finding a constructive proof of the fundamental theorem of algebra. He presented his solution, that amounts in modern terms to a combination of the Durand–Kerner method with the homotopy continuation principle, in 1891. Another proof of this kind was obtained by Hellmuth Kneser in 1940 and simplified by his son Martin Kneser in 1981.

Without using countable choice, it is not possible to constructively prove the fundamental theorem of algebra for complex numbers based on the Dedekind real numbers (which are not constructively equivalent to the Cauchy real numbers without countable choice[3]). However, Fred Richman proved a reformulated version of the theorem that does work.[4]

Proofs

All proofs below involve some analysis, at the very least the concept of continuity of real or complex functions. Some also use differentiable or even analytic functions. This fact has led some to remark that the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra is neither fundamental, nor a theorem of algebra.

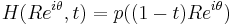

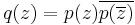

Some proofs of the theorem only prove that any non-constant polynomial with real coefficients has some complex root. This is enough to establish the theorem in the general case because, given a non-constant polynomial p(z) with complex coefficients, the polynomial

has only real coefficients and, if z is a zero of q(z), then either z or its conjugate is a root of p(z).

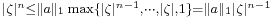

A large number of non-algebraic proofs of the theorem use the fact (sometimes called “growth lemma”) that an n-th degree polynomial function p(z) whose dominant coefficient is 1 behaves like zn when |z| is large enough. A more precise statement is: there is some positive real number R such that:

when |z| > R.

Complex-analytic proofs

Find a closed disk D of radius r centered at the origin such that |p(z)| > |p(0)| whenever |z| ≥ r. The minimum of |p(z)| on D, which must exist since D is compact, is therefore achieved at some point z0 in the interior of D, but not at any point of its boundary. The minimum modulus principle implies then that p(z0) = 0. In other words, z0 is a zero of p(z).

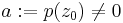

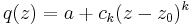

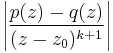

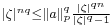

A variation of this proof that does not require the use of the minimum modulus principle (most of whose proofs in turn require the use of Cauchy's integral theorem or some of its consequences) is based on the observation that for the special case of a polynomial function, the minimum modulus principle can be proved directly using elementary arguments. More precisely, if we assume by contradiction that  , then, expanding

, then, expanding  in powers of

in powers of  we can write

we can write

Here, the  's are simply the coefficients of the polynomial

's are simply the coefficients of the polynomial  , and we let

, and we let  be the index of the first coefficient following the constant term that is non-zero. But now we see that for

be the index of the first coefficient following the constant term that is non-zero. But now we see that for  sufficiently close to

sufficiently close to  this has behavior asymptotically similar to the simpler polynomial

this has behavior asymptotically similar to the simpler polynomial  , in the sense that (as is easy to check) the function

, in the sense that (as is easy to check) the function  is bounded by some positive constant

is bounded by some positive constant  in some neighborhood of

in some neighborhood of  . Therefore if we define

. Therefore if we define  and let

and let  , then for any sufficiently small positive number

, then for any sufficiently small positive number  (so that the bound

(so that the bound  mentioned above holds), using the triangle inequality we see that

mentioned above holds), using the triangle inequality we see that

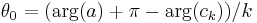

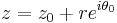

When r is sufficiently close to 0 this upper bound for |p(z)| is strictly smaller than |a|, in contradiction to the definition of z0. (Geometrically, we have found an explicit direction θ0 such that if one approaches z0 from that direction one can obtain values p(z) smaller in absolute value than |p(z0)|.)

Another analytic proof can be obtained along this line of thought observing that, since |p(z)| > |p(0)| outside D, the minimum of |p(z)| on the whole complex plane is achieved at z0. If |p(z0)| > 0, then 1/p is a bounded holomorphic function in the entire complex plane since, for each complex number z, |1/p(z)| ≤ |1/p(z0)|. Applying Liouville's theorem, which states that a bounded entire function must be constant, this would imply that 1/p is constant and therefore that p is constant. This gives a contradiction, and hence p(z0) = 0.

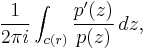

Yet another analytic proof uses the argument principle. Let R be a positive real number large enough so that every root of p(z) has absolute value smaller than R; such a number must exist because every non-constant polynomial function of degree n has at most n zeros. For each r > R, consider the number

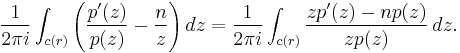

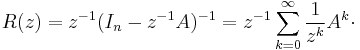

where c(r) is the circle centered at 0 with radius r oriented counterclockwise; then the argument principle says that this number is the number N of zeros of p(z) in the open ball centered at 0 with radius r, which, since r > R, is the total number of zeros of p(z). On the other hand, the integral of n/z along c(r) divided by 2πi is equal to n. But the difference between the two numbers is

The numerator of the rational expression being integrated has degree at most n − 1 and the degree of the denominator is n + 1. Therefore, the number above tends to 0 as r tends to +∞. But the number is also equal to N − n and so N = n.

Still another complex-analytic proof can be given by combining linear algebra with the Cauchy theorem. To establish that every complex polynomial of degree n > 0 has a zero, it suffices to show that every complex square matrix of size n > 0 has a (complex) eigenvalue[5]. The proof of the latter statement is by contradiction.

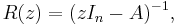

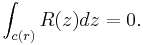

Let A be a complex square matrix of size n > 0 and let In be the unit matrix of the same size. Assume A has no eigenvalues. Consider the resolvent function

which is a meromorphic function on the complex plane with values in the vector space of matrices. The eigenvalues of A are precisely the poles of R(z). Since, by assumption, A has no eigenvalues, the function R(z) is an entire function and Cauchy's theorem implies that

On the other hand, R(z) expanded as a geometric series gives:

This formula is valid outside the closed disc of radius ||A|| (the operator norm of A). Let r > ||A||. Then

(in which only the summand k = 0 has a nonzero integral). This is a contradiction, and so A has an eigenvalue.

Topological proofs

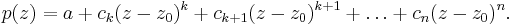

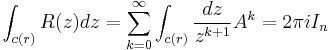

Let z0 ∈ C be such that the minimum of |p(z)| on the whole complex plane is achieved at z0; it was seen at the proof which uses Liouville's theorem that such a number must exist. We can write p(z) as a polynomial in z − z0: there is some natural number k and there are some complex numbers ck, ck + 1, ..., cn such that ck ≠ 0 and that

It follows that if a is a kth root of −p(z0)/ck and if t is positive and sufficiently small, then |p(z0 + ta)| < |p(z0)|, which is impossible, since |p(z0)| is the minimum of |p| on D.

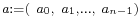

For another topological proof by contradiction, suppose that p(z) has no zeros. Choose a large positive number R such that, for |z| = R, the leading term zn of p(z) dominates all other terms combined; in other words, such that |z|n > |an − 1zn −1 + ··· + a0|. As z traverses the circle given by the equation |z| = R once counter-clockwise, p(z), like zn, winds n times counter-clockwise around 0. At the other extreme, with |z| = 0, the “curve” p(z) is simply the single (nonzero) point p(0), whose winding number is clearly 0. If the loop followed by z is continuously deformed between these extremes, the path of p(z) also deforms continuously. We can explicitly write such a deformation as  where t is greater than or equal to 0 and less than or equal to 1. If one views the variable t as time, then at time zero the curve is p(z) and at time one the curve is p(0). Clearly at every point t, p(z) cannot be zero by the original assumption, therefore during the deformation, the curve never crosses zero. Therefore the winding number of the curve around zero should never change. However, given that the winding number started as n and ended as 0, this is absurd. Therefore, p(z) has at least one zero.

where t is greater than or equal to 0 and less than or equal to 1. If one views the variable t as time, then at time zero the curve is p(z) and at time one the curve is p(0). Clearly at every point t, p(z) cannot be zero by the original assumption, therefore during the deformation, the curve never crosses zero. Therefore the winding number of the curve around zero should never change. However, given that the winding number started as n and ended as 0, this is absurd. Therefore, p(z) has at least one zero.

Algebraic proofs

These proofs use two facts about real numbers that require only a small amount of analysis (more precisely, the intermediate value theorem):

- every polynomial with odd degree and real coefficients has some real root;

- every non-negative real number has a square root.

The second fact, together with the quadratic formula, implies the theorem for real quadratic polynomials. In other words, algebraic proofs of the fundamental theorem actually show that if R is any real-closed field, then its extension  is algebraically closed.

is algebraically closed.

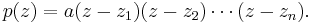

As mentioned above, it suffices to check the statement “every non-constant polynomial p(z) with real coefficients has a complex root”. This statement can be proved by induction on the greatest non-negative integer k such that 2k divides the degree n of p(z). Let a be the coefficient of zn in p(z) and let F be a splitting field of p(z) over C; in other words, the field F contains C and there are elements z1, z2, ..., zn in F such that

If k = 0, then n is odd, and therefore p(z) has a real root. Now, suppose that n = 2km (with m odd and k > 0) and that the theorem is already proved when the degree of the polynomial has the form 2k − 1m′ with m′ odd. For a real number t, define:

Then the coefficients of qt(z) are symmetric polynomials in the zi's with real coefficients. Therefore, they can be expressed as polynomials with real coefficients in the elementary symmetric polynomials, that is, in −a1, a2, ..., (−1)nan. So qt(z) has in fact real coefficients. Furthermore, the degree of qt(z) is n(n − 1)/2 = 2k − 1m(n − 1), and m(n − 1) is an odd number. So, using the induction hypothesis, qt has at least one complex root; in other words, zi + zj + tzizj is complex for two distinct elements i and j from {1,...,n}. Since there are more real numbers than pairs (i,j), one can find distinct real numbers t and s such that zi + zj + tzizj and zi + zj + szizj are complex (for the same i and j). So, both zi + zj and zizj are complex numbers. It is easy to check that every complex number has a complex square root, thus every complex polynomial of degree 2 has a complex root by the quadratic formula. It follows that zi and zj are complex numbers, since they are roots of the quadratic polynomial z2 − (zi + zj)z + zizj.

J. Shipman showed in 2007 that the assumption that odd degree polynomials have roots is stronger than necessary; any field in which polynomials of prime degree have roots is algebraically closed (so "odd" can be replaced by "odd prime" and furthermore this holds for fields of all characteristics). This is the best possible, as there are counterexamples if a single prime is excluded.

Another algebraic proof of the fundamental theorem can be given using Galois theory. It suffices to show that C has no proper finite field extension.[6] Let K/C be a finite extension. Since the normal closure of K over R still has a finite degree over C (or R), we may assume without loss of generality that K is a normal extension of R (hence it is a Galois extension, as every algebraic extension of a field of characteristic 0 is separable). Let G be the Galois group of this extension, and let H be a Sylow 2-group of G, so that the order of H is a power of 2, and the index of H in G is odd. By the fundamental theorem of Galois theory, there exists a subextension L of K/R such that Gal(K/L) = H. As [L:R] = [G:H] is odd, and there are no nonlinear irreducible real polynomials of odd degree, we must have L = R, thus [K:R] and [K:C] are powers of 2. Assuming for contradiction [K:C] > 1, the 2-group Gal(K/C) contains a subgroup of index 2, thus there exists a subextension M of C of degree 2. However, C has no extension of degree 2, because every quadratic complex polynomial has a complex root, as mentioned above.

Corollaries

Since the fundamental theorem of algebra can be seen as the statement that the field of complex numbers is algebraically closed, it follows that any theorem concerning algebraically closed fields applies to the field of complex numbers. Here are a few more consequences of the theorem, which are either about the field of real numbers or about the relationship between the field of real numbers and the field of complex numbers:

- The field of complex numbers is the algebraic closure of the field of real numbers.

- Every polynomial in one variable x with real coefficients is the product of a constant, polynomials of the form x + a with a real, and polynomials of the form x2 + ax + b with a and b real and a2 − 4b < 0 (which is the same thing as saying that the polynomial x2 + ax + b has no real roots).

- Every rational function in one variable x, with real coefficients, can be written as the sum of a polynomial function with rational functions of the form a/(x − b)n (where n is a natural number, and a and b are real numbers), and rational functions of the form (ax + b)/(x2 + cx + d)n (where n is a natural number, and a, b, c, and d are real numbers such that c2 − 4d < 0). A corollary of this is that every rational function in one variable and real coefficients has an elementary primitive.

- Every algebraic extension of the real field is isomorphic either to the real field or to the complex field.

Bounds on the zeroes of a polynomial

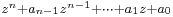

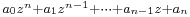

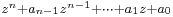

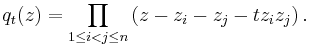

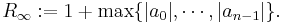

While the fundamental theorem of algebra states a general existence result, it is of some interest, both from the theoretical and from the practical point of view, to have information on the location of the zeroes of a given polynomial. The simpler result in this direction is a bound on the modulus: all zeroes  of a monic polynomial

of a monic polynomial  satisfy an inequality

satisfy an inequality  where

where

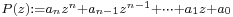

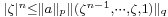

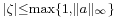

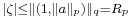

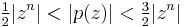

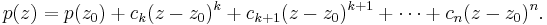

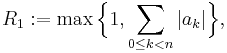

Notice that, as stated, this is not yet an existence result but rather an example of what is called an a priori bound: it says that if there are solutions then they lay inside the closed disk of center the origin and radius  . However, once coupled with the fundamental theorem of algebra it says that the disk contains in fact at least one solution. More generally, a bound can be given directly in terms of any p-norm of the n-vector of coefficients

. However, once coupled with the fundamental theorem of algebra it says that the disk contains in fact at least one solution. More generally, a bound can be given directly in terms of any p-norm of the n-vector of coefficients  , that is

, that is  , where

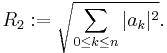

, where  is precisely the q-norm of the 2-vector

is precisely the q-norm of the 2-vector  , q being the conjugate exponent of p, 1/p + 1/q = 1, for any

, q being the conjugate exponent of p, 1/p + 1/q = 1, for any  . Thus, the modulus of any solution is also bounded by

. Thus, the modulus of any solution is also bounded by

for  , and in particular

, and in particular

The case of a generic polynomial of degree n,  , is of course reduced to the case of a monic, dividing all coefficients by

, is of course reduced to the case of a monic, dividing all coefficients by  . Also, in case that 0 is not a root, i.e.

. Also, in case that 0 is not a root, i.e.  , bounds from below on the roots

, bounds from below on the roots  follow immediately as bounds from above on

follow immediately as bounds from above on  , that is, the roots of

, that is, the roots of  . Finally, the distance

. Finally, the distance  from the roots

from the roots  to any point

to any point  can be estimated from below and above, seeing

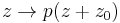

can be estimated from below and above, seeing  as zeroes of the polynomial

as zeroes of the polynomial  , whose coefficients are the Taylor expansion of

, whose coefficients are the Taylor expansion of  at

at

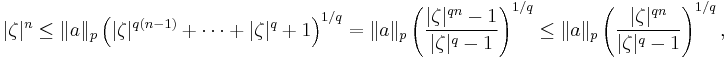

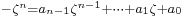

We report the here the proof of the above bounds, which is short and elementary. Let  be a root of the polynomial

be a root of the polynomial  ; in order to prove the inequality

; in order to prove the inequality  we can assume, of course,

we can assume, of course,  . Writing the equation as

. Writing the equation as  , and using the Hölder's inequality we find

, and using the Hölder's inequality we find  . Now, if

. Now, if  , this is

, this is  , thus

, thus  . In the case

. In the case  , taking into account the summation formula for a geometric progression, we have

, taking into account the summation formula for a geometric progression, we have

thus  and simplifying,

and simplifying,  . Therefore

. Therefore  holds, for all

holds, for all

- See also Properties of polynomial roots, for further results about the location of zeroes.

Notes

- ↑ See section Le rôle d'Euler in C. Gilain's article Sur l'histoire du théorème fondamental de l'algèbre: théorie des équations et calcul intégral.

- ↑ Concerning Wood's proof, see the article A forgotten paper on the fundamental theorem of algebra, by Frank Smithies.

- ↑ For the minimum necessary to prove their equivalence, see Bridges, Schuster, and Richman; 1998; A weak countable choice principle; available from [1].

- ↑ See Fred Richman; 1998; The fundamental theorem of algebra: a constructive development without choice; available from [2].

- ↑ A proof of the fact that this suffices can be seen here.

- ↑ A proof of the fact that this suffices can be seen here.

References

Historic sources

- Cauchy, Augustin Louis (1821), Cours d'Analyse de l'École Royale Polytechnique, 1ère partie: Analyse Algébrique, Paris: Éditions Jacques Gabay (published 1992), ISBN 2-87647-053-5 (tr. Course on Analysis of the Royal Polytechnic Academy, part 1: Algebraic Analysis)

- Euler, Leonhard (1751), "Recherches sur les racines imaginaires des équations", Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences et des Belles-Lettres de Berlin (Berlin) 5: 222–288, http://bibliothek.bbaw.de/bbaw/bibliothek-digital/digitalequellen/schriften/anzeige/index_html?band=02-hist/1749&seite:int=228. English translation: Euler, Leonhard (1751), "Investigations on the Imaginary Roots of Equations" (PDF), Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences et des Belles-Lettres de Berlin (Berlin) 5: 222–288, http://www.mathsym.org/euler/e170.pdf

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1799), Demonstratio nova theorematis omnem functionem algebraicam rationalem integram unius variabilis in factores reales primi vel secundi gradus resolvi posse, Helmstedt: C. G. Fleckeisen (tr. New proof of the theorem that every integral rational algebraic function of one variable can be resolved into real factors of the first or second degree).

- C. F. Gauss, “Another new proof of the theorem that every integral rational algebraic function of one variable can be resolved into real factors of the first or second degree”, 1815

- Kneser, Hellmuth (1940), "Der Fundamentalsatz der Algebra und der Intuitionismus", Mathematische Zeitschrift 46: 287–302, ISSN 0025-5874 (The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra and Intuitionism).

- Kneser, Martin (1981), "Ergänzung zu einer Arbeit von Hellmuth Kneser über den Fundamentalsatz der Algebra", Mathematische Zeitschrift 177: 285–287, ISSN 0025-5874 (tr. An extension of a work of Hellmuth Kneser on the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra).

- Ostrowski, Alexander (1920), "Über den ersten und vierten Gaußschen Beweis des Fundamental-Satzes der Algebra", Carl Friedrich Gauss Werke Band X Abt. 2, http://gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de/dms/load/img/?PPN=PPN236019856&DMDID=dmdlog53 (tr. On the first and fourth Gaussian proofs of the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra).

- Weierstraß, Karl (1891). "Neuer Beweis des Satzes, dass jede ganze rationale Function einer Veränderlichen dargestellt werden kann als ein Product aus linearen Functionen derselben Veränderlichen". Sitzungsberichte der königlich preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. pp. 1085–1101. (tr. New proof of the theorem that every integral rational function of one variable can be represented as a product of linear functions of the same variable).

Recent literature

- Fine, Benjamin; Rosenber, Gerhard (1997), The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-94657-3

- Gersten, S.M.; Stallings, John R. (1988), "On Gauss's First Proof of the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra", Proceedings of the AMS 103 (1): 331–332, doi:10.2307/2047574, ISSN 0002-9939, http://jstor.org/stable/2047574

- Gilain, Christian (1991), "Sur l'histoire du théorème fondamental de l'algèbre: théorie des équations et calcul intégral", Archive for History of Exact Sciences 42 (2): 91–136, doi:10.1007/BF00496870, ISSN 0003-9519 (tr. On the history of the fundamental theorem of algebra: theory of equations and integral calculus.)

- Netto, Eugen; Le Vavasseur, Raymond (1916), "Les fonctions rationnelles §80–88: Le théorème fondamental", in Meyer, François; Molk, Jules, Encyclopédie des Sciences Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées, tome I, vol. 2, Éditions Jacques Gabay, 1992, ISBN 2-87647-101-9 (tr. The rational functions §80–88: the fundamental theorem).

- Remmert, Reinhold (1991), "The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra", in Ebbinghaus, Heinz-Dieter; Hermes, Hans; Hirzebruch, Friedrich, Numbers, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 123, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-97497-2

- Shipman, Joseph (2007), "Improving the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra", Mathematical Intelligencer 29 (4): 9–14, doi:10.1007/BF02986170, ISSN 0343-6993

- Smale, Steve (1981), "The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra and Complexity Theory", Bulletin (new series) of the American Mathematical Society 4 (1)

- Smith, David Eugene (1959), A Source Book in Mathematics, Dover, ISBN 0-486-64690-4

- Smithies, Frank (2000), "A forgotten paper on the fundamental theorem of algebra", Notes & Records of the Royal Society 54 (3): 333–341, doi:10.1098/rsnr.2000.0116, ISSN 0035-9149

- van der Waerden, Bartel Leendert (2003), Algebra, I (7th ed.), Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-40624-7

External links

- Fundamental Theorem of Algebra — a collection of proofs

- D. J. Velleman: The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra: A Visual Approach, PDF (unpublished paper), visualisation of d'Alembert's, Gauss's and the winding number proofs

- Fundamental Theorem of Algebra Module by John H. Mathews

- Bibliography for the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra

- From the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra to Astrophysics: A "Harmonious" Path

|

|||||||||||

![\begin{align}

|p(z)| &< |q(z)| + r^{k+1} \left|\frac{p(z)-q(z)}{r^{k+1}}\right|\\[.2em]

&\le \left|a +(-1)c_k r^k e^{ i(\arg(a)-\arg(c_k))}\right| + M r^{k+1} \\[.5em]

&= |a|-|c_k|r^k + M r^{k+1}.

\end{align}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/935d5c932e8be3478b7f753286bf2087.png)

![R_p:= \biggl[ 1 + \Bigl(\sum_{0\leq k<n}|a_k|^p\Bigr)^{q/p}\biggr]^{1/q},](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/d15834ff18bd14e42c445de1b3cb1096.png)